Foodborne Illness Can Induce Autoimmune Illnesses

FOOD SAFETY AND QUALITY

Foodborne illnesses represent a significant public health challenge in the United States and the world. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), each year there are 47.8 million cases of foodborne illnesses causing 128,000 hospitalizations, 3,030 deaths, and $78 billion in costs (including costs attributed to premature deaths, medical expenses, and loss of productivity). Unspecified pathogens cause 80% of foodborne illnesses, and known pathogens (21 bacteria, five viruses, and five parasites) cause 20% of the illnesses.

Ninety percent of all foodborne illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths in the United States caused by known pathogens have been linked to seven microorganisms (Scallan et al. 2015): Campylobacter sp., Clostridium perfringens, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella (non-typhoidal), norovirus, and Toxoplasma gondii. Of these pathogens, Salmonella was determined to be the principal cause of hospitalization and death, and norovirus was estimated to cause the most foodborne illnesses.

How Pathogens Contaminate Food

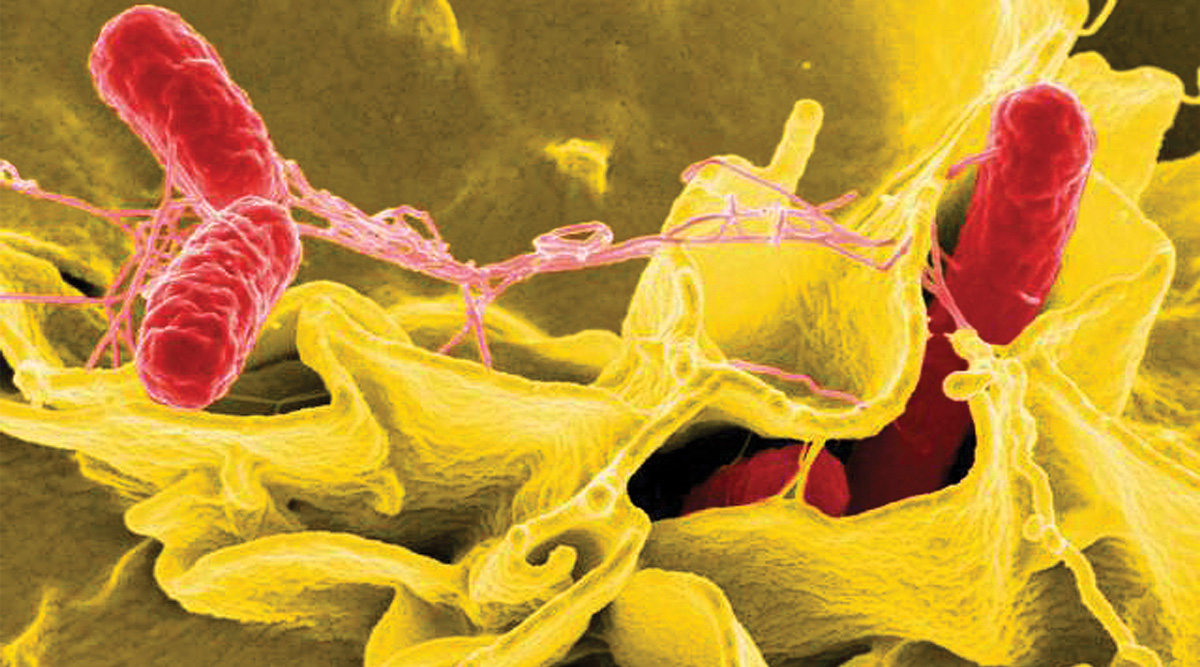

Salmonella causes about 1.35 million infections, 26,500 hospitalizations, and 420 deaths in the United States every year. And many U.S. foodborne illness outbreaks linked to cut fruit, ground beef, papayas, frozen raw tuna, pre-cut melons, and ground turkey are caused by Salmonella. Salmonella continues to be a significant human pathogen in the United States and the world for many reasons: Salmonella spp. are ubiquitous in the environment; poultry and eggs are the main reservoirs. Intensive agricultural practices employed in the beef, pork, and poultry industries in many countries of the world lead to the spread of Salmonella spp. among food animals and thus animal-based food products. These agricultural practices include, but are not limited to, raising large numbers of animals in small animal facilities, unsatisfactory hygiene and sanitation on animal farms, and incorporation of slaughterhouse by-products into animal feeds among other practices. International seafood and aquaculture industries are not immune to the challenges associated with Salmonella. Salmonella spp. can be present in many water environments that are subject to fecal contamination. Feeds used by the aquaculture industry, especially in developing countries, may include raw animal-based or contaminated ingredients. Finally, Salmonella spp. outbreaks have also been linked to a large variety of fresh and processed fruits and vegetables grown under various climates. Salmonella contamination can originate practically anywhere along the farm-to-fork continuum for produce, including irrigation water, soil, fertilizer, wind, birds, insects, pets, and wild animals.

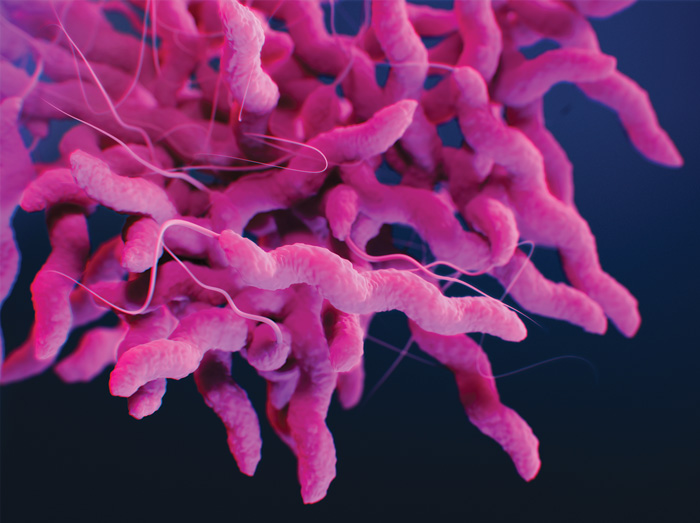

Campylobacter causes an estimated 1.5 million illnesses each year in the United States. Various wild and domesticated animals—birds, cows, horses, sheep, pigs, rabbits, poultry, rodents, and household pets—serve as reservoirs of Campylobacter jejuni for human disease. Contaminated produce, meat, and seafood can also be the source of Campylobacter infections. Raw, under-cooked, or improperly handled cooked poultry; raw or under-pasteurized milk; and contaminated/untreated water are the most commonly identified sources of Campylobacter outbreaks. Poultry harbor various bacteria on skin, feathers, and feet. Some of these organisms are naturally present on poultry. Poultry is also subject to contamination during harvesting and chilling of carcasses. It is critical to chill the carcasses very rapidly in a facility with appropriate hygiene and sanitation to avoid bacterial growth.

Salmonella spp. and Campylobacter often enter food processing plants through raw materials, but they can also enter food processing plants via healthy workers (dirt/soil on clothing, shoes, vehicles, etc.) and human carriers. Many foodborne pathogens, including C. jejuni and Salmonella Typhimurium, can attach to various surfaces (processing equipment, walls, floors, drains, etc.) in food processing plants and form biofilms in areas that are difficult to reach and clean. A biofilm is an accumulation of microbial cells into complex structures on solid surfaces through complicated multistep processes. Appropriate cleaning can ensure that the cells present in growing biofilms can be reached by sanitizers. Microbial cells present in mature biofilms tend to be more resistant to sanitizers than individual cells.

Long-Term Sequalae From Foodborne Illness

Scallan et al. (2015) estimated that every year more than 200,000 Americans develop long-term sequalae—a condition that is the consequence of a previous illness—from a single bout of foodborne illness. Several human organ systems can be affected by long-term sequelae, including the cardiovascular, endocrine, digestive, hepatic, immune, and respiratory systems. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), reactive arthritis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome are examples of long-term sequelae (Batz et al. 2013, Kowalcyk and Batz 2018). It may take days, weeks, or years for long-term sequelae to appear in the human body. Therefore, it can be highly challenging for medical professionals to properly diagnose, control, and treat the long-term sequelae of foodborne illnesses. A comprehensive understanding of the long-term sequelae is critical not only for effective treatment of patients but also for establishing successful policies in public health and ensuring food safety.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), IBS is a common condition that affects the large intestine, causing a mix of various symptoms, including abdominal cramping, bloating, and changes in bowel habits. IBS is difficult to diagnose, control, and treat. Diet, stress management, probiotics, and medication are generally used to control IBS symptoms. Kowalcyk and Batz (2018) report that IBS affects 10%–20% of the global population. The foodborne pathogens Escherichia coli, Yersinia, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Shigella, norovirus, Giardia, and Trichinella cause 17% of all IBS cases. Campylobacter may induce development of celiac disease in individuals susceptible to IBS (Kowalcyk and Batz 2018).

The immune system is a complex network of cells, tissues, and organs that work together to recognize and defend against undesirable invaders, thus protecting the human body from infections and other illnesses. If the immune system cannot do its job for some reason, disorders of the immune system arise, including allergies, asthma, and autoimmune diseases. Autoimmune diseases can cause the immune system to attack healthy cells and tissues. Scallan et al. (2015) estimated that every year 33,000 Americans end up with reactive arthritis (an autoimmune disease) after foodborne illnesses. According to the NIH, reactive arthritis is pain and /or swelling in the knees, ankles, or feet caused by an infection somewhere else in the body. Additional symptoms may include red/swollen eyes and a swollen urinary tract. Kowalcyk and Batz (2018) indicate that microorganisms associated with reactive arthritis include Campylobacter (3%–13% of cases), E. coli O157:H7 (up to 9% of cases), Salmonella (2%–15% of cases), Shigella (up to 10% of cases), and Yersinia (up to 14% of cases). Brucella, C. difficile, Cryptosporidium, Giardia, Staphylococcus, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus can also lead to reactive arthritis.

Guillain-Barré syndrome is a rare neurological disorder; it causes the body’s immune system to erroneously attack part of the peripheral nervous system. The peripheral nervous system is the network of nerves located outside of the brain and spinal cord. Approximately 40% of all individuals diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome per year in the United States have Campylobacter as the common trigger for the disease (Kowalcyk and Batz 2018). In a recent study, Scallan Walter et al. (2020) explored the incidence of Campylobacter-associated Guillain-Barré syndrome estimated from health insurance data. The results indicated that Campylobacter accounts for up to 41% of all cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Who’s at Risk

Any individual can end up with long-term sequalae of foodborne illness, but some individuals are more susceptible. The majority of individuals recover at home from foodborne illness with plenty of rest, rehydration, and care from family and friends. However, the young, the elderly, the immunocompromised, and pregnant and postpartum women are at greater risk for a severe bout of foodborne illness. At-risk individuals should seek early medical attention in the event that they experience serious symptoms of foodborne illness, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, bloody diarrhea, and abdominal pain, and flu-like symptoms. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration offers consumer education for individuals at risk for acute foodborne illness and long-term sequalae. Various other organizations also provide information on food safety, including kitchen hygiene/sanitation, proper food handling, food recalls, foodborne illness symptoms, and how to get tested for foodborne illness.

Most of the concern about foodborne illness concentrates on acute illness. But more research is needed to better understand the mechanisms by which the immune system is triggered by foodborne illness agents. Also needed is more dependable epidemiological and economic data on long-term sequelae to foodborne illness. The resulting data could be used for evaluation of strategies to reduce the occurrence of foodborne illness in the United States and the world.

REFERENCES

Batz, M.B., E. Henke, and B. Kowalcyk. 2013. Long-term consequences of foodborne infections. Infec. Dis. Clin. North Am. 27(3): 599–616.

Kowalcyk, B. and M. Batz. 2018. “Health at Risk: Long-Term Health Effects of a Foodborne Illness.” Partnership for Food Safety (webinar). http://www.fightbac.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/FINAL-Long-Term-Effects-of-Foodborne-Illness.pdf

Scallan, E., R.M. Hoekstra, B.E. Mahon, et al. 2015. An assessment of the human health impact of seven leading foodborne pathogens in the United States using disability adjusted life years. Epidemiol. Infect. 143(13): 2795–2804.

Scallan Walter, E.J., S.M. Crim, B.B. Bruce, et al. 2020. Incidence of Campylobacter-Associated Guillain-Barré Syndrome Estimated from Health Insurance Data. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 17(1): 23–28.